New Year, new me

March 13, 2023

The concept of making a New Year’s resolution has been a tradition in the Western World for a very long time. Whether people actually stick to their resolution or not, it’s always fun to set a goal for yourself at the beginning of a new year. The most frequently made resolutions include improving mental health, improving fitness, losing weight, improving diet and improving finances.

“My resolution was to become healthier and stronger,” Leela Sandler, freshman, said. “I’ve definitely followed through on it because I practice soccer most days and go to the gym. I’ve also been eating a lot of protein and healthy foods.”

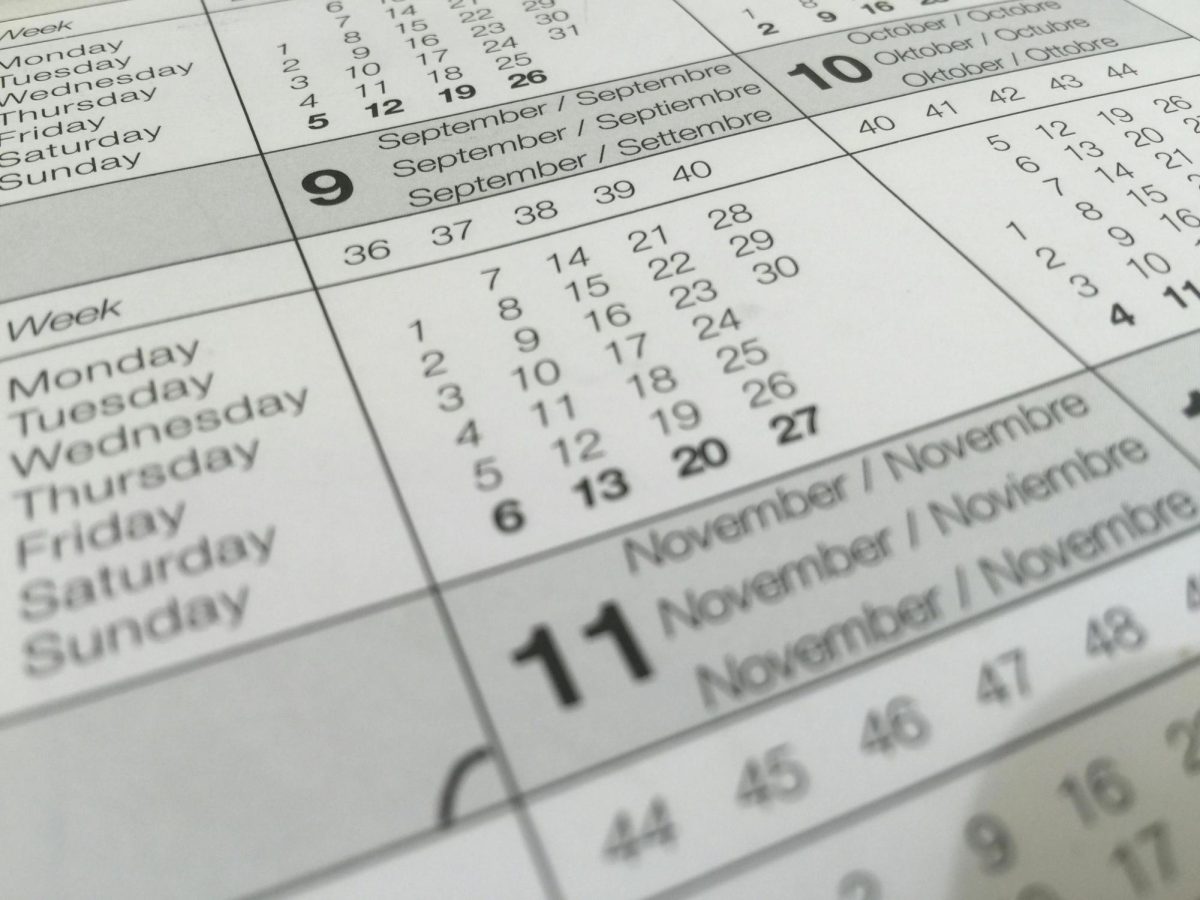

The history of New Year’s resolutions dates all the way back to around 2000 B.C. The ancient Babylonians are said to have been the first people to make resolutions, and they were also the first group to hold recorded celebrations of the new year. However, their new year began in mid-March, when they planted their crops, instead of on January 1. Their celebration was known as Akitu, a massive 12-day religious festival where they crowned a new king or reaffirmed their loyalty to the currently reigning king. They would also make promises to the gods to repay their debts or return any items they had borrowed, which were their versions of New Year’s resolutions. If the Babylonians kept their word, their pagan gods would bestow favor on them for the coming year. If not, they would fall out of the gods’ favor.

Similarly, Julius Caesar of ancient Rome tinkered with the calendar and established January 1 as the beginning of a new year in 46 B.C. January, which was named after Janus, the two-faced god whose spirit inhabited doorways and arches, held special significance for the Romans. They believed that Janus looked symbolically both backwards into the previous year and ahead into the year to come. They celebrated by offering sacrifices to the deity and made promises of good conduct for the coming year, similar to the resolutions we make today.

The tradition started to resemble more of what we practice today around 1740. For the early Christains, the first day of the new year became the traditional occasion for thinking about one’s past mistakes and resolving to do better in the future. The English clergyman John Wesley, founder of Methodism, created the Covenant Renewal Service, which was most commonly held on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s day. They included readings from Scriptures and sang hymns to serve as a spiritual alternative to the raucous celebrations usually held to celebrate the new year. This is still a common tradition today, as many evangelical Protestant churches hold such services on New Year’s Eve to pray and make resolutions for the new year.

While the roots of New Year’s resolutions are religious, it is now more of a secular practice for most people. Instead of making promises to gods or deities, people mainly make promises to themselves about self-improvement. However, if you don’t keep your resolution, you’re not the only one. Research shows that about 45 percent of Americans make resolutions, but only 8 percent actually carry them out. This unbalanced ratio probably won’t stop people from making them, though, as it’s a tradition that’s been about 4,000 years in the making.

“When people make resolutions, they shouldn’t just limit it to New Year’s,” Sandler said. “I think you can start a resolution any time in the year, and people should be more motivated to do that. Most of my resolutions were goals I’d started before the new year, and just continued to work on.”